Innovation – Where are you placed on the spectrum?

We all know the saying, “Nothing changes if nothing changes”. And if nothing changes, we remain the same. We don’t address failures of the past or exploit the opportunities of the future. We don’t grow. We don’t progress. We don’t get better.

As we note in our guide Outcome-led procurement: A common sense approach to construction procurement, Albert Einstein defined insanity as “doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result”.

Innovation, which breaks that repetitive and to many a largely unsatisfying cycle, is the focus of Martyn Jones’ Thought for the Month.

What is it? We talk a lot about it and the term innovation is thrown about widely and promiscuously. The most common and widely accepted definition is the application of new ideas.

But this is not sufficiently nuanced to be particularly helpful in understanding and managing innovation generally or in the context and culture of construction. Let’s explore some important elements of innovation.

The first, is that it’s important! It’s the essential means by which organisations – and indeed whole industries such as construction – change, survive and thrive.

Innovation is both an outcome and a process. The innovative outcomes that have received the most attention in the past have been improved products, followed by improved processes and trailing some distance behind these, services.

These all remain important but innovation is also to be found in new markets, new ways of organising and operating, and new ways of fashioning the means to add value in business propositions and models.

We also need to be aware of the nature and dynamics of innovation and the myriad of contextual factors that shape innovation choices, including historical, social, economic, cultural, political, technological and legal.

A combination of both demand and supply is seen as a determinant of successful innovation.

Innovation is a multi-factor process depending on collaborative intra- and inter-organisational relationships.

Innovations cluster together to create new technological-economic-social paradigms

There is a significant spatial or geographical dimension to innovation with links between innovation and regional support and learning.

These elements shape the strategies and practices decision-makers use to decide what innovations to pursue, develop, implement and sustain in order to add value to their endeavours – which might include better economic performance, corporate and supply chain competitiveness and productivity, environmental sustainability, and in our case the quality of the built environment and the wellbeing of users.

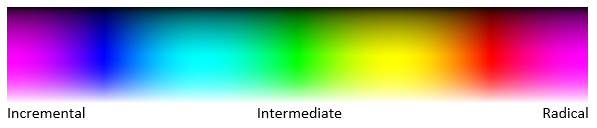

And there’s the scope of innovations to consider too. At the incremental end of the spectrum innovations occur in established markets, technologies, and ways of doing things that are close to existing practices.

At the other end of the spectrum, radical innovations involve breakthroughs in markets, technologies and ways of doing things very different from current practices. They are rare, largely unknowable but highly consequential.

Between these two levels on the innovation spectrum is the fertile ground that promises many substantial innovations that build on existing products, practices and technologies, but extends them and diversifies them into new ventures and areas.

But our innovative ambitions need to be tempered by the matter too of the risks, costs, uncertainties and timescales associated with innovation, the extent of which will depend upon the ambition and amplitude of the innovation.

Another consideration for the fervent innovator: The best returns on their innovation may not actually be accrued by them for their risky endeavours but by those who emulate, copy and follow them.

Another difficulty facing the innovator is that decision-making necessary for innovation will often conflict with the deeply embedded financial objectives, routines and incentives found in and between most organisations including those in construction’s organisations, project teams and supply chains. Innovation requires collaboration across those professional and organisational boundaries, and routines with a tolerance of possible failure that most of construction clients and suppliers find difficult to accept.

All of these factors need to be taken into account in deciding what innovation to pursue and how to lead and manage the innovation process.

Despite all these challenges, innovation can be highly stimulating and rewarding for those involved. And it is desperately needed too, particularly in dealing with the current climate crisis and other pressing issues associated with the emerging paradigm.

And, encouragingly for those daunted by the prospect of innovation, most innovations spring from the body of materials, experiments, ideas developed in previous innovative efforts so that most innovation involves new combinations of existing elements, bodies of knowledge or technology,

Given the immense challenges we now face in the built environment we need to shift from doing everyday things better (although recent events revealing construction’s difficulties with compliance show there’s considerable scope for that too) to those intermediate levels of innovation that through significant changes in resources and capabilities can add new solutions to existing problems.

But how do we go about manging innovation? That will be the focus of my next Thought for the Month.

Article by Martyn Jones